Teachers’ Guide

Multimedia Links

-

An extensive bio of Irena Klepfisz can be found at the Jewish Women’s Archive. She was listed as one of Forward 50 Influential American Jews in 2019 as the “trailblazing lesbian poet, intellectual and political activist, and the keeper of the Bundist flame.” That same year, she was also named one of the 2019 Sexiest Jewish Intellectuals Alive.

-

Excerpts of the Wexler Oral History Project’s interview with Irena Klepfisz shed light on her life and oeuvre: she talks about her father, Michał Klepfisz, and his role in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (3:09 min); the traumatic experience of being a Holocaust survivor and American Holocaust memorials (5:53); her path to Yiddish-English poetry (6:55), and her work on the rediscovery of Yiddish Women Writers and her identity (6:56).

-

In 2017, Irena Klepfisz did a reading tour in Poland for the first time, and here she talks about the experience of being celebrated as a poet in the country of her birth (7:22).

-

Irena Klepfisz discusses her life journey, poetry, and activism in a recent Yiddish-English interview for Vaybertaytsh: A Feminist Podcast in Yiddish (2019).

-

Irena Klepfisz in conversation with Agi Legutko, reflecting on the 1995 "Di Froyen" conference, and the growing prominence of Yiddish women writers, translators, artists, and scholars, from the beginnings of the modern feminist movement until today, at the Yiddish Book Center event, Di Froyen: Celebrating the Women of Yiddish Literature, November 4, 2022.

Bibliography

-

To read more of Klepfisz’s poetry, see Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems 1971-2021 (2022). For her non-fiction prose, see her essay on “Secular Jewish Identity: Yidishkayt in America” in The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology (1989).

-

Klepfisz wrote an influential introduction, “Queens of Contradiction: A Feminist Introduction to Yiddish Women Writers” to Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers (1994), and also published an essay collection, Dreams of An Insomniac: Jewish Feminist Essays, Speeches, and Diatribes (1990), which includes essays on the Holocaust, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, class and lesbian Jewish identity. Her most recent essay on Yiddish culture and women writers: “The 2087th Question or When Silence Is the Only Answer” appeared online in In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies (2020).

-

For a discussion of “Bashert” and Klepfisz’s poetry, see Adrienne Rich’s introduction to A Few Words in the Mother Tongue: Poems Selected and New (1971-1990) (1990); and an interview with Irena Klepfisz in Meaning and Memory: Interviews with Fourteen Jewish Poets (2001, 233-254).

-

For scholarship on Klepfisz, see Laurence Roth, “Pedagogy and the Mother Tongue: Irena Klepfisz’s ‘Di Rayze Aheym/The Journey Home’” in Symposium (1999, 52:4, 269-78), and Zohar Weiman-Kelman, “Legible Lesbian Lines: The Bilingual Poetry of Irena Klepfisz” in Journal of Lesbian Studies (23:1, 2019, 21-35). An early but extensive critical and bibliographical entry on Irena Klepfisz can be found in American Jewish Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook (1994).

Teaching Resources

1. Defining Bashert

The Yiddish word “bashert” means “(pre)destined.” It has entered the English vocabulary through Yiddish and is often used to reference what is meant to be or to refer to a predestined lover or soul mate.

Suggested Activity: Ask students if they have heard the word “bashert” previously and, if so, to write down what they think it means and then share it with the group. Then show students the dictionary entries and ask them to compare their guesses with the definitions. If they haven’t heard the word before, simply show them the dictionary definitions and discuss.

Having established the definition of the word, ask students to make guesses about what the poem they are about to read will be about, knowing that it has a Yiddish title.

A follow-up activity: After the students have read the entire poem (Activity 5), have them come back to their definitions and consider whether their perception of the word has changed. How does the notion of “bashert” change our understanding of the fate of the Holocaust victims and survivors? Does predestination end with the Holocaust or does it go beyond? If you were to write a new definition of the word “bashert” based on the poem, what would it be?

Source: Comprehensive Yiddish-English Dictionary verterbukh.org

2. Dedications to "Bashert," read by Irena Klepfisz, 2017, video

This artistic audio-video collage was originally prepared for the poet’s so-called “Bashert Tour” in Poland, the first official celebration of Irena Klepfisz’s poetry in the country of her birth in 2017.

Suggested Activity: Show the video featuring an artistic collage with Irena Klepfisz reading the dedications to “Bashert.” Ask students to take note of phrases that stand out and that repeat. Then ask the following questions: What might these long dedications be about? Knowing a bit about Klepfisz’s history, do you think this is about the Holocaust? Why or why not? And what do you think of the video artist’s visual choices? What is the significance of the forest? Is there a change in tone, colors, etc. between the dedications to those who died and those who survived?

Source: Gabi von Seltman, “BASHERT by Irena Klepfisz,” The Art, History & Apfelstrudel Foundation in co-production with JCC Warsaw, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpsTgaAFuHk

3. Dedications to "Bashert"

Sinister Wisdom, where the poem first appeared, is a leading lesbian literary and art journal that has created a multicultural and multi-class lesbian space to explore diverse lesbian experiences since its establishment in 1976. It publishes four issues a year and continues to be a primary source on lesbian culture in America.

Suggested Activity: Ask students to read the text of the dedications and to answer the following questions: What genre do these dedications fall into: poetry, elegy, prayer, litany, mantra, philosophical treatise, or something else? Who is the speaker and who is the addressee? What is the impact of the repetitions “these words are dedicated to those…” “because” on the audience? Which parts seem to apply specifically to the Holocaust? How does the poet define death and life at the end of each dedication?

Then divide students into groups and ask them to list the reasons given in the dedications for why someone died or survived. Then ask them to focus on those that appear to be both reasons why people died and reasons why people survived. What do these contradictions within the dedications tell us about the meaning of “bashert” in the poem?

Source: Sinister Wisdom 21 (1982), and in Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems 1971-2021 (2022).

(Permission granted by the poet.)

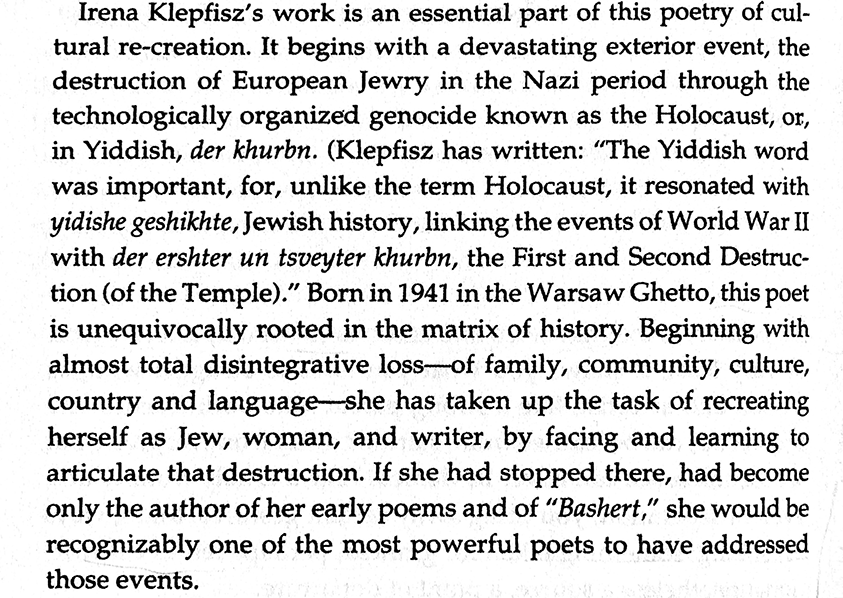

4. Text excerpt, Adrienne Rich’s Introduction to Irena Klepfisz’s A Few Words in the Mother Tongue

Adrienne Rich’s introduction sets the context for Klepfisz’s collection of selected poems. Rich provides a historical background by contemplating late twentieth-century developments in North American poetry, which had by then been increasingly written by poets who did not have the privilege of “inherit[ing] an uninterrupted and recognized culture,” and who shared an affiliation with more than one historic legacy.

Suggested Activity: Ask students to read the scholarly excerpt. What are Adrienne Rich’s insights in this section of the text? What does she mean by “poetry of cultural re-creation”? How do you understand Rich’s argument that Klepfisz “is unequivocally rooted in the matrix of history”? Do you agree with the statement that even if she wrote only “Bashert,” Klepfisz “would be recognizably one of the most powerful poets to have addressed [the Holocaust]”?

Source: Adrienne Rich, Introduction, A Few Words in the Mother Tongue: Poems Selected and New (1971-1990) (1990), p. 14.

5: The entire poem

Irena Klepfisz, Bashert

The critical focus has been on the dedications to “Bashert,” rather than on the entire poem. In conjunction with the dedications, the poem creates an innovative composition, thus challenging a conventional understanding of poetry, and exploring the concept of “bashert” at a more profound level.

Suggested Activity:

Divide students into four groups and ask each group to first read the entire poem and then focus on one assigned part of the poem, and think about the following questions: What is the genre of the poem? The poet refers to it as “a narrative poem,” while Adrienne Rich calls it “a poem unlike any other … in its form, in its verse and prose rhythms …” (Introduction, 21). How does the unique form of the poem impact your reception? Rich also labels it as “one of the great ‘borderland’ poems” – what do you think that means? How does the main poem relate to the dedications to those who died and those who survived?

Questions for specific groups are below. This activity can be used in a follow-up class.

Group 1: What is the significance of the protagonist’s mother’s chance meeting with a fellow Jew in Part 1 (“Poland, 1944”)?

Group 2: What does the poet mean by “history demanding a response” and “The Holocaust without smoke” in Part 2 (“Chicago, 1964”)?

Group 3: When does the protagonist become “equidistant from two continents” in Part 3 (“Brooklyn, 1971”)? What is the culminating moment for the protagonist’s identity?

Group 4: Who is “a keeper of accounts” in Part 4 (“Cherry Plain, 1981”)? How does the protagonist approach embracing her historical legacy?

End the discussion with the following questions: What is the legacy of each continent? How does Elza’s story connect all parts of the poem? “Bashert” is the only Yiddish word in the entire poem. Why? The title of the last section of the poem is also the title of Klepfisz’s second volume of poetry, Keeper of Accounts. What do you think is the significance of that?

Source: Entire text can be found in Sinister Wisdom 21 (1982), and in Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems 1971-2021 (2022).

(Permission granted by the poet.)